Tony Trabert – Memories of My Friend – Television commentator and Tennis camp organizer

As the great Tony Trabert passed away on the last February, Tennis Chalk has the absolute honor to publish his long story, written by Mark Winters, who was probably in life one of the best friends of Tony. In order to keep content readable, enjoyable, and time affordable, Tennis Chalk has split the long article into episodes. The fourth episode starts from 1971, when Tony embarked in a career as CBS commentator for tennis and golf, and describes deeply his role as tennis camp organizer at the Thacher School.

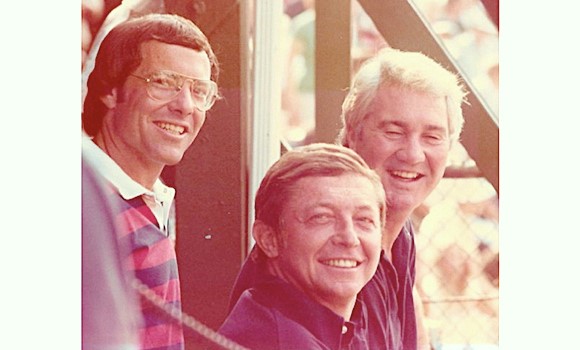

As good as the previous year was, 1971 was more fulfilling for Trabert. He embarked on a career as a CBS tennis and golf analysist. For 30 years, most of which he teamed with Pat Summerall, the former New York Giants football player, he was the voice of US Open television broadcasts. In addition, for over 20 years he was a member of the Australian Channel 9 team at Roland Garros and Wimbledon.

The “Tennis Boom” in the US originated in the 1970s. Trabert took advantage of the trend and launched the Tony Trabert Tennis Camp at The Thacher School, (whose most worthy alumnus then was Howard Hughes) in Ojai, California. It was located at the base of the Los Padres National Forest. At the time, it was a private boys boarding school. More important, it had dormitories and ten tennis courts. As an aside, Ojai means “Moon” which comes from the Chumash Tribe’s language.

At the time, I was a fledgling journalist who was freelancing tennis along with wine and travel stories, as well as coaching. Basically, I was deciding what I was going to be when I grew up. As mentioned, I had met Trabert in the ‘60s. Our paths had crossed from time to time until the spring of 1971 when he offered me a position at the camp.

Annually for many years, thereafter, I lived, for ten weeks in the early summer, when the weather was very warm, at Thacher. A week was spent getting to know the staff and going over the Trabert way of teaching. Three three-week camp sessions followed that and were open to youngsters from ages nine to 18.

Because of his presence and his easygoing manner, Trabert was an icon, and that was the reason students came from across the US as well as around the world. Unlike many “name camps” where the “name” was rarely on hand, Tony was always there. What’s more, his approach to teaching didn’t require instructors or students to understand the complexity of the inverse angle of a hypotenuse or for that matter any mathematical gradients. He believed – The simpler, the better. It was all a matter of getting the racquet head (and hand) behind and below the ball and lifting it over the net. The more movement and flourishes that were added, the more errors could result.

In his dealings with the campers and parents (and the staff, too), he was honest, sincere and had a wicked sense of humor. Trabert dealt with people with big money, who sent their children to camp, the same way he did with those who just wanted their youngster to develop a fundamental foundation for his/her game, with concern and care. It was almost as if he was a favorite uncle when it came to his manner of communicating. What he said didn’t require an interpreter. His words had meaning. Yet, thinking back – I still marvel. He was completely egoless. I really believe that those who attended the camps, along with many on the staff, didn’t fully comprehend how great a player he was… To everyone, he was “Tone” or “T2” and he was perfectly comfortable with that.

I, in turn, was “Marko” and looking at mental photos from those days always results in good feelings. The second Sunday of every camp session was “Parents Day” when fathers and mothers would visit. Some had significant celebrity or business status. Many were just “folks”. Most everyone wanted to play doubles with or against Trabert. Occasionally, recent college graduates, who had a brother or sister attending the session and seemed to have majored in “tennis”, would appear. They would strut around the doubles court anxious to take on “The Master” and to prove they were, indeed, players.

It was a foolish move. I never, in all the years that I played with him in these matches, understood why “ego overwhelmed sensibility”. Trabert was so comfortable with who he was, and his game was so complete, he would simply enjoyed the moment…then hit another winner.

On one occasion, we were warming up and I had been attempting to “lift” the ball, so I didn’t drive a barrage of pre-match shots into the net. I had been accomplishing the task, carrying many groundstrokes a foot or so over the baseline.

After we had taken our warm-up serves, Tone turned to me and with a sly grin said, “Marko, you have been getting good depth on your groundies. But, when we play, it is okay to hit them inside the white lines…” I guess I had been tight because I didn’t want to embarrass him by knocking down the net as we got loose. His comment, though, cracked me up and I had a relaxing laugh. (As, it turned out, we won handily no thanks to me. What’s more, he could still “play”. In fact, at the 1972 US Open, he and Seixas lost a tough 6-4, 6-4, 4-6, 6-3 contest to Savitt and Sammy Giammalva, Sr. at Forest Hills and this was after preparing by playing doubles every day, during the campers rest period, with one of the counselors against me and another instructor.)

When talk turns to the best backhand of all-time, many purists continue to claim that Don Budge’s was the best. Stan Wawrinka of Switzerland and Richard Gasquet of France have also been recognized. But, for me Trabert’s was top of the line. I wasn’t bad at doubles primarily because off the ad side of the court I could crease cross-court backhand serve returns. Nonetheless, before playing camp visitors, we had a regular routine. (I smile as I write this.) Tone would say, “You know, Marko you have a great forehand so I think you should play the deuce side against these guys…and the first time they serve to your backhand hit it down-the-line at the net man…that will send a message. Then I will see what I can do…”. Of course, he kindly overlooked the fact that my going inside out on a backhand return from that side of the court was something that I had to pray to accomplish…while his play off the ad side of the court was unmatched.

The Thacher campus is 427 acres in a rustic area covered in trees, grass and wild plants. There was plenty of “territory” for youngsters to explore during their three-week visits. They were warned the first evening at Introductory Night about curfew, daily rest hour and mealtimes. There were a few other rules, foremost of which was staying out of the forest that surrounded the camp because the poison oak and nettles were hazardous. This was stressed again and again.

Yet, for countless campers, the forest became an “it will not happen to me challenge”. On one occasion, a teenage boy and girl were immediately smitten when they checked into camp. They became inseparable, so it was hardly a surprise that they went exploring. The boy ended up with poison oak all over his body and spent the entire three weeks in the infirmary. She didn’t get a case as serious, so her tennis was only somewhat limited. It was hardly a surprise that when Trabert learned about the result of the “hike” in tennis shorts, he told the youngster he could attend the second session at no cost so he could actually play some tennis (and stop being slathered in Calamine lotion).

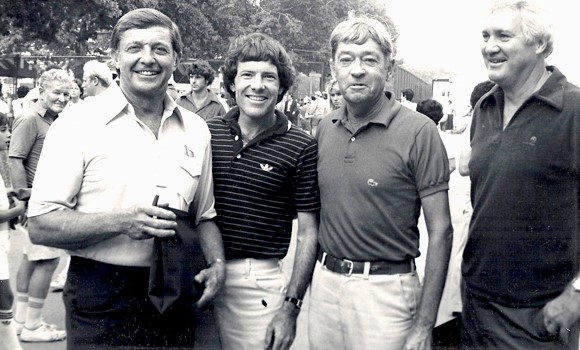

As my tennis writing assignments increased, I regularly attended the US Open. Whether it was at Forest Hills or at the National Tennis Center (before Billie Jean King’s name was attached) in Flushing Meadow – Corona Park, I was able to spend time with Trabert and Summerall. The last year the tournament was played at the Westside Tennis Club in 1977 offer some wonderful recollections.

Tony and Pat’s friendship went beyond their time in the broadcast booth. On an afternoon during the first week of the tournament, I caught up with them just after they finished broadcasting a match, played on the 14,000 seat-center court. I had been watching the contest and Tony caught my eye as they were signing-off and signaled to meet them at the bottom of the stairs behind the booth.

As they came down from their perch, four boys, who appeared to be between 10 and 12-years-old, came running up. Being true to their youth, they bounced around anxiously waiting for their heroes. Clutching their autograph books and ballpoint pens, they jockeyed for position. Their leader, speaking in a loud voice that was a cross between Vinnie Barbarino’s “Welcome Back, Kotter” character and Barbra Streisand’s Brooklynese, began yelling, “Toe-nee, Toe-nee, ma matha luvs yuh… Pa’t, Pa’t yuh wer’ah dah best kick-a dah Ji’ants (He played football for the New York Giants) eva hadt…” Trabert signed for the first boy who moved to Summerall while boy number two attacked Tony.

We had been planning to get a quick snack because they had matches to call later in the day. Watching the autograph interaction, I started to back away. As I did, the leader of the boys spotted me and figured since I was with Tony and Pat, I must be somebody. Realizing that he was coming toward me I began to backup more quickly. Either I was slow, or he was very anxious to add another autograph to his collection. All of sudden he was on top of me thrusting his autograph book in my face. I told him he didn’t want my autograph. I wasn’t anyone of importance… and continued to backpedal. I glanced at Tony who was signing for the third boy, and he looked over at me, smiled and gave me a – Go ahead – nod.

Embarrassed, I took the book and ballpoint and signed my name. By that time, the second boy was on top of me, and I began to sign again. In the meantime, the kid who had Tony and Pat’s autographs on separate pages in his book turned to mine, looked at it and bellowed – “Mak Win’tah, Hay, Who Dah Hell Ah Yuh?” He then took the page I had signed, ripped it out of his book, tore it into tiny pieces and threw them back at me. By the time my shredded autograph hit the ground, I had begun to laugh. I laughed so hard that I had tears running down my checks.

This happened at the end of the first week of the tournament. During the rest of the event, if we were alone after our conversation had ended, Tony would quietly say – “Hay, Who Dah Hell Ah’ Yuh?” (And it still makes me chuckle.)

Trabert first played the US National Championships just after he turned 18 in 1948. He reached the third-round losing to Earl Cochell, the No. 9 seed, 6-0, 6-3, 3-6, 6-4. A must mention aside, three years later [1951] the talented but behaviorally erratic Cochell was suspended for life by the USLTA, (which became the USTA in 1975), after a multitude of incidents in a 4-6, 6-2, 6-1, 6-2 fourth round match he lost to Mulloy.

During his amateur career, Trabert competed at Forest Hills seven times. By 1977, the exclusive Westside Tennis Club, located in a well-to-do neighborhood, had established a tradition. It hosted the championships for more than 60 years. The facility had become antiquated and didn’t have the necessary adjacent property to become a site capable of hosting the expanding Open.

Finding a new location to host the championships’ fortnight had been discussed by USTA officials for some time. But as Kelleher had commented about tennis administrators being “little more than shoe clerks”, nothing was done. That was until William Ewing (Slew) Hester became USTA President in 1977.

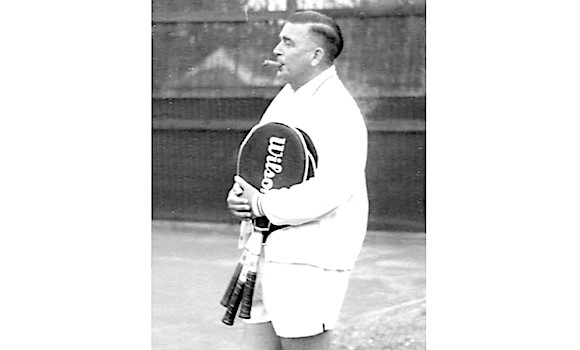

Flying into New York for a USTA Board meeting, about to land at LaGuardia Airport, he happened to glance out the airplane window and saw the snow-covered Singer Bowl ruin, (which had become the Louis Armstrong Memorial Stadium in 1973), where the 1964-65 World Fair had been held. Hester was big and bold. He was Babe Ruth in size and like the baseball great, he was fond of cigars and sour-mash whiskey. An all-around athlete in college, his on court skills were first-rate. During his competitive years, he won more than 500 local and national tennis titles. Delightfully candid, he once admitted that he liked to drink all night and play tennis all day.

Being from miniscule Hazlehurst, Mississippi, Hester spoke “Southern” with an accent that was so syrupy he could have been a “Gone With The Wind” cast member. A savvy salesman, he had made a fortune as a “wildcatter”, selling interests in prospective oil wells.

The smooth-talking Hester knew deal making and he was shrewd. He approached the City of New York and negotiated an arrangement for the 16-acre facility that resulted in a $10 million dollar refurbishing by the USTA. Armstrong Stadium was turned into a 20,000-seat arena (the largest in tennis at the time), with a 6,000 seat Grandstand Court alongside, as well as 25 additional courts.

He had promised that Flushing Meadow – Corona Park would be ready to host the 1978 Open. It was…barely. There were a lot of steel girders visible when the tournament began and landscaping was, in reality, not existent. When criticized, he responded in true Hester fashion – “If people want tradition, I’ll plant some ivy”. It is important to point out that attendance in the inaugural year at Flushing Meadow – Corona Park was 275,300, or roughly 57,000 more than it had been at the Forest Hills farewell.

By now, those who have continued to read my story are asking – What does this have to do with Tony Trabert? Here is the answer…

Every afternoon prior to the dinner hour, Hester could be found sitting in a corner of “Slew’s Place”, the restaurant/bar named for him at the “new” Open. He would sit there regaling anyone – actually, almost everyone – who passed by with updates on the day’s action.

He and Trabert had a warm relationship. Because of the friendship, Tony (often with Pat) would spend some of his television break time at Slew’s Place. It was a comfortable spot where he could escape, relax and enjoy himself because “Slew” was the show. Tony regularly gave me an “if you are free…” heads up – Meet me in front of the door to Slew’s.

It was like being invited to attend a session of the Tennis UN. Slew simply being Slew held court while “names in the game” circulated. Because of Trabert, I had access. Later in the tournament, when I would show up before he arrived, those monitoring the door would recognize me as “Tone’s doubles partner…” and let me enter. Though I could add more about my experiences the first year at Slew’s, this story is about Tony Trabert…

Hester envisioned turning the final major of the year into the best tournament in the world. It was his goal-driven focus. Forty-three years later, it seems he achieved it. Sadly, few remember his name, let alone give him kudos for his foresight.

Hester was inducted into the International Tennis Hall of Fame in 1981. His biography notes, “The new facility was aptly called, ‘The House that Slew Built’.” He passed away in 1993 at the age of 81.